The Stars (Still) Look Very Different Today

Tuesday, January 10, 2017 at 8:35PM

Tuesday, January 10, 2017 at 8:35PM Four minutes and thirteen seconds into the blue-eyed soul of "Young Americans," just before its exuberant coda, the instrumentation abruptly falls away. For a couple of freely floating measures, all that remains is the pleading voice of David Bowie, slipping in and out of time and posing a question as though everything depended on the answer: "Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?"

It’s impossible to encapsulate an artist in a single album or song, much less in a single line. But on record, those seven seconds capture something close to the essence of Bowie. The voice: impeccably cool, yet on the verge of breaking. The words: immediate, impassioned and yearning.

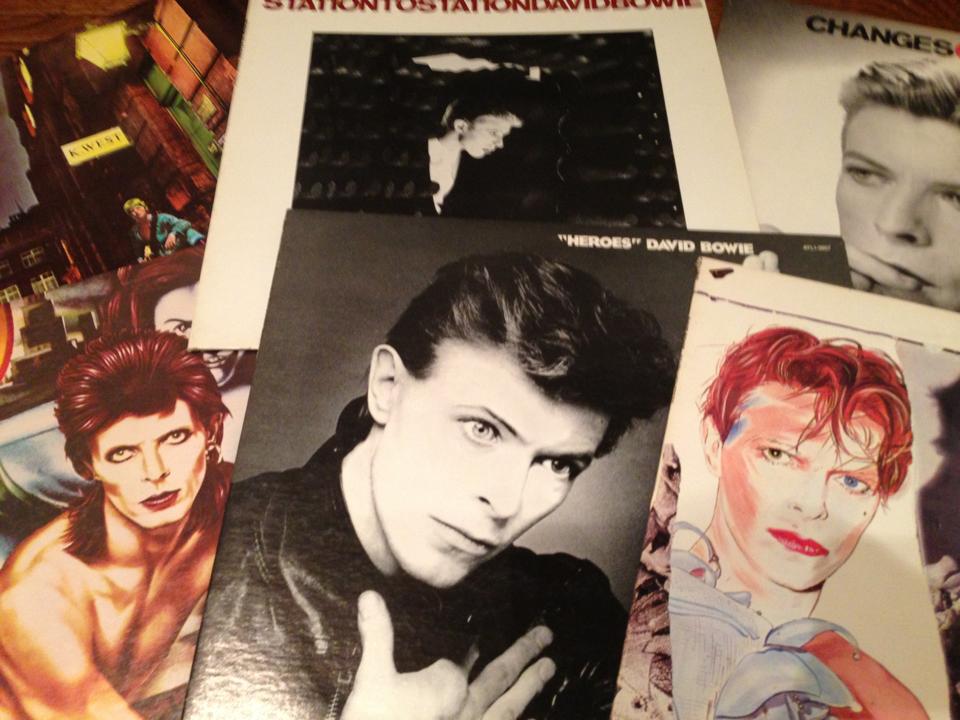

To have been truly touched by Bowie’s music is to know that the answer to that question, timeless as it may be, really isn’t important—but that asking it means everything. Because at its heart, the great and enduring theme of his work, from "Space Oddity" to "Lazarus," was to explore and to feel the full extent of our humanness—however raw, messy, strange and beautiful it may be—and, ultimately and through it, to discover our humanity. Or, in his own words (from the title track of Station to Station): "Here are we, one magical moment—such is the stuff from where dreams are woven."

The outpouring in the wake of his passing made it perfectly clear: Through his music and his reinvention, Bowie had resonated with countless young people who sought nothing more than to connect and to feel connected amid the uncertainty of finding themselves and their place in this world. To lose him was to lose the wellspring of music that tempered our imperfection with the wonderful possibility of what we could become. And to accept that he was gone was cause to revisit the hopes and dreams of the younger selves he had inspired.

When David Bowie left this planet last January 10, we didn’t just lose a towering figure from the last half-century of popular music—we lost our last, great Romantic, a modern-day kindred spirit of Shelley, Keats, and Blake (who once even took on a persona named Screaming Lord Byron, for good measure).

Unlike his musical contemporaries who obsessively turned their attention inward or around them, Bowie alone, it seemed, looked upward—for inspiration, for confirmation, for absolution. He sang of starmen and spacemen, of angels and devils—yet created songs as rich as novels, populated by characters as detailed as they were universal, as alien and exotic as they were familiar. He enjoyed the riches of commercial success, but—ars longa, vita brevis—never at the expense of his art. And through all of his endeavors he reminded us that living life itself is—can be, should be—an artistic act, ultimately impermanent and flawed but full of grace, beauty, and truth.

These days, of course, we need all the grace, beauty and truth we can get. Fortunately, David Bowie left us enough to last a lifetime, if we listen closely.

Todd Christopher | Comments Off |

Todd Christopher | Comments Off |